Elliott Burns, Jen MacLachlan and Jake Charles Rees, Graduate Teaching Assistants on BA (Hons) Culture, Criticism and Curation, Central St Martins

This paper considers the pedagogical prototype, Everybody Phones Out (EPO), that took place between February - April 2016 on the BA (Hons) Culture, Criticism and Curation course at Central Saint Martins. EPO utilised a dedicated Instagram account, as a means to support the delivery of a series of traditional lectures to first year undergraduate students. Taking EPO as a case study this paper assesses the potential for IBMSNs (image-based-mobile-social-network) to be employed in, and beyond, the classroom for the delivery of content and engagement with students. This paper makes specific reference to EPO's co-option of the iconography of memes, the combination of textual and visual information and the image parlance of memeology to humorous, and virulent, affect. Evaluating our own successes and failures, we detail a code of conduct for others considering Instagram usage in education.

social media, Instagram, digital, memes, post-Internet, mobile phones

In January 2016 Stephanie Dieckvoss, stage one leader of BA (Hons) Culture, Criticism and Curation at Central Saint Martins, invited us to run four discussion sessions for her students to supplement their lecture programme. Our response was Everybody Phones Out (EPO) (Figure 1), a micro-syllabus on the social media platform Instagram, with the aim of exploring internet art after 2008, the notoriously-termed ‘Post-Internet’ moment.

EPO started as a play on the clichéd call, spoken at the start of class, ‘Everybody: phones away’. EPO was intended as a critique; questioning the standard assumption that electronic technologies distract students from matters-at-hand. It was also a play upon another standard classroom call, ‘Everybody: pencils out’. By replacing ‘pencils’ with ‘phones’ the project recognises one technology’s wane in relation to the other’s rise. The sessions sought to marry the subject matter taught on the course with technology, embracing social media as a teaching mechanism.

A dedicated EPO Instagram account ‐ @everybodyphonesout ‐ was set-up and run in parallel to the four lessons. The sessions responded directly to the topics covered in the following weekly lectures on the BA (Hons) Culture, Criticism and Curation course:

A further fifth session was later added. On Wednesday 27 April 2016 students presented personal / group projects responding to EPO. The project was optional, yet engagement and the resulting projects were of a very high level. One project was selected for an upcoming exhibition at the CSM Victorian Vitrine Gallery and has received other external interest.

EPO was open to 20 students out of a cohort of approximately 60, yet, in total 22 students attended. At the beginning of the sessions, students were asked whether they wanted the EPO Instagram account to remain private or public, the class was also asked whether they would permit us to use comments they made in the writing of this paper. Students unanimously voted for a public account and agreed for us to use any comments made (these have been anonymised).

This paper explains the process employed by EPO and details our use of Instagram, both inside and outside the classroom. In the conclusion, we detail possibilities for future use of social media as an educational platform. A glossary of terms can be found at the end.

The initial premise of EPO asked whether a learning strategy might integrate itself into the lived activities of students. Could ‘Image Based Mobile Social Networks’ (IBMSNs) serve as a means to deliver educational content? Our rationale for employing Instagram was simple: the art and topics we wanted to address often feature on Instagram. What originated as a quip developed legs. In our initial meeting we outlined a method of distributing course information via a dedicated Instagram account, which would act as a form of database for the project. Retrospectively, the process for designing each session can be distilled into 5 steps:

A second database of students’ Instagram accounts was created, allowing us to @ particular students in EPO Instagram posts. Typically we @’d 3 or 4 students at a time, and would ask them a pertinent question connected to the topics of each EPO class. Our rationale for this was that theoretically, learning about our students would inform better student engagement, creating a feedback-loop and making the Instagram account a more profitable learning ecosystem.

Beyond the interactive framework of speaking directly to students and eliciting broader responses through @’s, we experimented with other uses of Instagram, exploring whether it could act as a place to review a lesson, to inform students as to the location of the next class, be integrated into class activities, or solicit engagement with artists. Another approach involved @ing artists’ Instagram accounts in posts, which resulted in several artists and galleries (as well as other members of the Insta-verse) becoming followers and occasionally conversing with us.

Given our short timeframe, EPO had to develop in a responsive manner. The experimental nature of the initiative afforded little opportunity for reviewing and refining our strategies, therefore, the EPO account is best considered as a snapshot of techniques that might inform other curriculum design.

Memes featured heavily within EPO’s methodology. The term ‘meme’ was coined by evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins, in his book The Selfish Gene (1976). Dawkins hypothesised memes as ideas, behaviours, styles and skills that spread from person to person within a culture. Memes ‘travel longitudinally down generations, but they travel horizontally too, like viruses in an epidemic’ (Dawkins in Blackmore, 1999, p.ix).

Thorston Botz-Bornstein continues with this horizontal and vertical conceptualisation of culture in his writing, outlining that we need to ‘stop talking about substantive and essentialized entities that used to be called “genes” and to talk instead of developments that take place in time as well as in a complex, multi-layered environment’ (2008, p.146). Susan Blackmore has suggested that memes may be the contributing factor in the development of language and the increased mental abilities displayed by Homo Sapiens, enshrining our ability to imitate each other, and evolve beyond our evolutionary peers (1999, p.9). Based upon Blackmore’s emphasis upon evolution, it follows that memes are part of our educational process and therefore fit within the classroom.

As internet culture spread across the globe during the 1990s, the term ‘meme’ was co-opted by emerging online cultures. The new ‘prosumer’ gave memes a tangible residence in the world: exhibited as an image with overlayed text. Typically this form of meme is humorous, relies on particular social understandings and is easy to adapt.

In EPO posts an extract from our reading list was selected and a corresponding visual image chosen. For example, the quote by Michael Connor ‐ ‘I think a lot of the best art of our time is out there waiting to be labeled as such by forward-thinking art bureaucrats’ (in Cornell, 2006). Connor’s quote was paired with an image of the character Hermes in cartoon series Futurama (Figure 2). A joke exists between the content of the quote and the content of the image, making both memorable.

EPO’s memes offered bite-sized introductions to the content of the course’s syllabus. 20 pages of reading might be condensed into a single image and using the Instagram post’s caption description section, it is possible to add reference information. Students could optionally follow Instagram readings with ‘actual’ readings. By employing memes, EPO’s Instagram account simultaneously acted as a bibliography to the syllabus.

EPO experimented with various means of integrating Instagram into the lesson structure. The first 3 lessons began with short introductory presentations, which approached that week’s subject matter from each tutors’ own personal perspective. These were followed by group tasks that employed Instagram as either a research, creation or documentation tool. The fourth session involved a group visit to the Whitechapel Gallery, where Instagram artists were shown and the medium was central to discussions. Whilst it would be incorrect to dramatise these as specifically orchestrated experiments, they have proven worthy of comment.

For artists such as Amalia Ulman, Instagram is increasingly becoming a location of artistic practice. Many young female artists gain considerable followings and Ulman has over 121,000 followers (see Ulman, 2016). Often the art made in this context reveals a level of disposable wealth and these actions are often defined as #feminism. Content from a single account such as Ulman’s provided a rich archive for discussion.

Our first lesson tasked students to explore an Instagram account in an academic manner, researching it and making a critical analysis. Groups of 2 or 3 were assigned the Instagram account of a young female artist and told to feedback their findings to the class. Instead of serving as a social space, ‘Instagram’ was repositioned as a research space.

During these group discussions, each Instagram account was viewed via projection. EPO tutors would respond to conversation by bringing up certain images, comments and Instagram pages. When employed as a non-linear ‘PowerPoint’ style presentation, Instagram proved versatile, engaging and humorous, drawing-out and unpacking difficult topics. Initially conceived as 30-minute activity, the conversations during the first session continued for a full hour, eventually halted by a fire alarm.

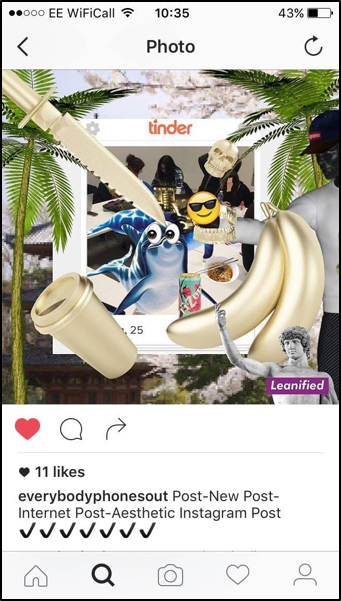

If EPO’s first task gauged students’ ability to navigate, read and interpret Instagram content, the second task required them to actively confront the medium by generating their own content. This second task invited students to reflect upon and reference current art trends, specifically responding to the over-use of ‘post’. Teams of students were given 30 minutes to craft their own Instagram post. The EPO tutors provided some encouragement and created their own post in a Blue Peter ‘here’s one I made earlier’ fashion.

EPO re-posted each response on to our account and students made brief presentations citing the aesthetic and conceptual rationale behind their image or video. The class (and members of the external public) could register their approval or disapproval by ❤ing or not ❤ing the post. An element of competition became important in EPO lessons. Once every group had presented, their respective scores of ❤s were counted and a winning team announced.

Instagram provided an informal, neutral ground, on which students and teachers could operate. Integrating social media into the classroom evened out hierarchical structures, allowing other relational forms to surface in the form of competition, antagonism and humour. Furthermore, the addition of a creative element generated visually and conceptually sophisticated responses.

Lessons 1 and 2 featured a small aspect of Instagram documentation, as images were posted and the creation task formed its own mini-record. However, only during the third session did we progress the techniques of documenting and posting as an in-classroom activity.

In this third session, students engaged in a hypothetical digital art auction. 12 lots were selected from the website Daata-Editions (Gryn, 2016). Auction brochures were made and handed out along with paddles adorned with the Instagram logo, and ❤ shaped currencies were distributed to the class (see Figure 4). Tutors acted as auction house staff and students played the bidders. The EPO Instagram account was to live stream information from the auction. Unfortunately, due to technical issues, live documentation did not work because two problems arose, one from the difficulties of touch typing on a smartphone and the second occurred because Instagram limits accounts to five successive comments.

Beyond the 3 planned in-class lessons, EPO arranged a class trip to visit the exhibition Electronic Superhighway at the Whitechapel Gallery. This final exercise had more to do with the curatorial practices surrounding digital and Instagram art. The exhibition was chosen due to its relevance to students, as it provided the opportunity to explore both artistic and curatorial practices. Also of note, is the fact that a work by Amalia Ulman was included in the exhibition. A group discussion followed the visit and the students were set an optional curatorial assignment to be completed over the Easter break.

The following sub-sections assess 5 EPO Instagram posts in relation to the strategy behind the taught sessions.

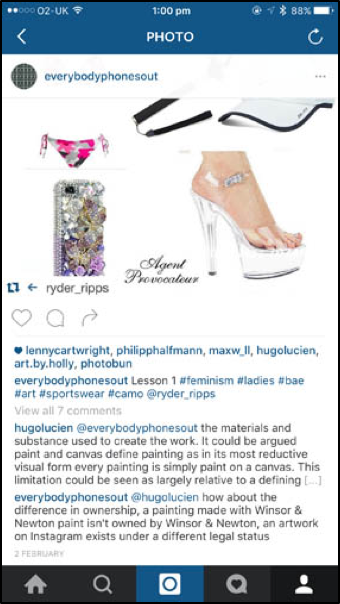

#feminism #ladies #bae #art #sportswear #camo @ryderripps

This first EPO post was re-posted from the artist Ryder Ripps’ Instagram feed (Ripps, 2015) (pictured Figure 5, Burns, MacLachlan and Rees, 2016b). Ryder’s post depicting a ‘Feminist Artist On Instagram Starter Pack’ (classed as a meme), was chosen for its critique of issues surrounding feminist art and specifically the artistic practices of young female ‘Insta-artists’. The deconstruction of this meme involved exploring linguistic aspects as well as the imagery depicted in this post and formed the basis for class activity.

Session 1 was on ‘Identity Politics and Feminist Art on Instagram’. It sought to facilitate critical discussion around these female artists through analysis of the concept underlying the imagery, and critique Instagram as a platform for displaying these images. Ripps’ meme and Amalia Ulmans’ work (2016; 2014) were central to the lecture, but it did include examples from other artists whose work related to the #s used in the EPO re-post: #feminism #ladies #bae #art #sportswear #camo. The theories discussed in the students ‘Culture Criticism and Curation’ lectures were thus applied to individual discussions and integrated into the group’s analysis.

In the pedagogical context, this Instagram post generated an interesting discussion during the lesson. To initiate conversations regarding Ripps’ ‘starter pack’ as an artistic medium, we posed the question ‘is Ryder Ripps dig at young female Instagram artists appropriate or just a cynical sexist response?’. On Instagram, one student responded with the comment: ‘a generalization of the aesthetic idiosyncrasies that define the medium, definitely cynical albeit a stretch for sexist’ (see Burns, MacLachlan and Rees, 2016b). Several comments followed, however, it was in the classroom that this conversation really developed. The post proved that the EPO tutors could reference posts in-class as a springboard to deeper conversation.

@amaliaulman #art #women #gyals #instagram

EPO’s second post led on from Ripps’ meme by re-posting an example of the artworks he critiqued. The purpose of this was to make a link between the theoretical elements deconstructed through Ripps’ meme and the issues surrounding actual artistic practice.

Amalia Ulman was a contentious figure within group discussions. Our re-post from her Instagram performance piece Excellences and Perfections (2014), was initially misunderstood by many as being a shallow indulgence rather than a serious legitimate artwork (Figure 6, Burns, MacLachlan and Rees, 2016c). By re-posting this image we intended to create a debate around female self-representation and we ensured that students were conscious of Ulman’s practice prior to the lesson.

Once EPO had posted the Ulman image, we @’ed 3 students posing the question, ‘when artwork and the culture it critiques are so inseparable can we see its feminist credentials?’ (Burns, MacLachlan and Rees, 2016c). Subsequently, during the course of the 10 exchanges that took place between EPO and the 2 students, a dialogue developed that integrated serious discussion ‐ ‘It’d be easy to see how insta-feminism could be considered faddish’ ‐ with cultural expressions ‐ ‘I feel the most appropriate response is a meme ‐ “why u mad tho”’ ‐ and friendly back and forths (see Burns, MacLachlan and Rees, 2016c). This fed into the classroom environment, with the students taking strong stances on issues during group discussions. The learning strategy was effective here, as students could interact with material in their daily comings and goings, for example, on a long bus ride home.

@ryantrecartin ‐ Centre Jenny

Preceding the second classroom session ‘Post-New Post-Internet Post-Aesthetics Instagram-Post’, a short clip of Ryan Trecartin’s video Centre Jenny (2013) was posted to the EPO feed (Figure 7). The post captured 15 seconds of the video: a fraction of the piece’s 53 minute 15 second running time.

This post aimed to inform students’ understanding of the genre of Post-Internet art and, by highlighting the practice of a particular artist, we hoped to initiate in-class discussions on the subject. However, no comments were made and most students did not seem aware of Trecartin’s practice at the beginning of the second session. The post only received three ❤s: one from a CSM tutor, another from an EPO lecturer and the third from Trecartin himself.

One success was that, as a result of the post, Trecartin started following the EPO Instagram account. The post itself, whilst limited in its engagement of students, reveals the potential of such open-access platforms to initiate conversations outside the classroom and engage with artists directly. EPO could have taken a more active role here by @ing students or attempting to converse with Trecartin. Whether this would have been successful as a learning tool is unfortunately unknowable.

#Repost @amaitriteparole_ @sara.frdv @everybodyphonesout #instafood #pizza #foodporn #tasty #lunch #realfood #homemade13

In session 2, EPO asked students to create an Instagram post responding to Post-Internet concepts. The winning team (@’d in the post) responded by printing a pixelated rendition of a slice of pizza, adding ketchup, eating it: posting a video of this final step (Ba, 2016; Burns, MacLachlan and Rees, 2016f). The students described how they had observed that the process of translating digital into physical and back again was a common characteristic of many Post-Internet artworks, and chose pizza because of its prevalence in many video games.

Instagram presents an efficient platform for gaining feedback and during the competition the class was to able to validate each other's work. As a means of determining the winner, students awarded ❤s to the posts they thought deserved it. The paper-pizza video post accumulated twenty-four ❤s, including several from outside the class (see Burns, MacLachlan and Rees, 2016f). The ‘gamification’ of this task enabled friendly and humorous competition amongst the students. The exercise proved extremely profitable as it allowed a group identity to form and explored aspects of Post-Internet art, cementing the students and tutors into a collective. Furthermore, the use of Instagram and EPO re-posting of student content, promoted the student's abilities and intelligence to the wider Insta-verse.

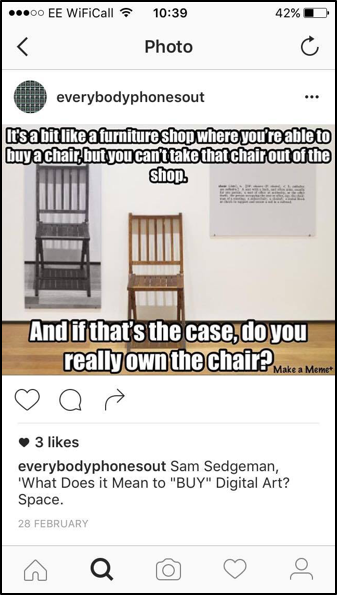

Sam Sedgman: ‘What Does it Mean to “BUY” Digital Art Space?’

EPO made a total of 31 meme posts. Our third session, on ‘E-commerce and the Digital Art Market’ dealt with the economies of digital art. In preparation, we paired an image by Joseph Kosuth, One and Three Chairs (1965), with a quotation from Sam Sedgman, in which he outlines the process of buying digital art as being ‘a bit like a furniture shop where you’re able to buy a chair, but you can’t take the chair out of the shop. And if that’s the case, do you really own the chair?’ (2015). The quote relays sceptical attitudes towards digital art, yet it is also rendered humorous by its relation to Kosuth’s work, which in itself questions the very nature of a chair (see Figure 8).

By using meme posts that juxtaposed sources and opinions, EPO was able to experiment with curriculum content and its creative delivery. However, the value of these outcomes in terms of student learning is dubious. The chair meme received three ❤s, with only 1 from an EPO student. Within the scope of this project’s aim to enhance student engagement, such a poor response could be considered a failure. We can speculate however, that other students may have seen the post and potentially, read the related article by Sedgman. The best result we can hope for is that the memes become a resource for students to return to in the future.

Drawing concrete conclusions about the effectiveness of EPO is problematic. As previously mentioned, the programme defies robust evaluation due to the potential inconsistencies involved with its socially reactive nature. Furthermore, our ‘precariat’ working status ‐ as guests who were invited to run an experimental programme ‐ involved a limited time-scale for the review of student responses. Whilst Instagram does have capacities for qualitative evaluation built-in, counting ❤s does not necessarily correlate to value. Over the course of the 4 classes, EPO made 136 posts, received 633 ❤s and drew 124 followers: without any concerted promotional campaign. It is difficult to judge what the true value of these numbers is. That the students commented at all indicates a level of engagement with the material, unfortunately this anecdotal evidence is hard to evaluate.

One obvious success of EPO has been the creation of a permanent, accessible resource for the students involved. Whilst posts were intended as discussion points, they may in fact work better as an archive of information, a series of signposts towards further reading. Furthermore, the EPO Instagram account with its use of meme visuals, created a form of bibliography that is easy to navigate and more memorable than a conventional list of written titles. It is likely that a few students did see every post, but most will be familiar with the account and at least, know of its existence. Therefore, we can hope that the students will return to the account in coming years, if they ever choose to write on a subject related to the posts and discussions it records.

The breadth of EPO’s content is also worth noting. A typical reading list may contain a couple of core resources with a half dozen further references. EPO did away with this format; instead, 10 quotes from 10 separate essays provide an introduction to a range of ideas and content. Admittedly the level of comprehension diminishes with this scattershot approach, yet there is potential to hit at least a few target students who have an interest in some of the focused subject points. To be successful EPO relies on the students’ personal interest and willingness to further their studies. Hopefully we have given them each something of interest to which they can refer and that will drawn their attention when undertaking practice and coursework assignments in the future.

Ultimately, the biggest success of EPO stems from the many ways in which students engaged with content in-classroom. From our personal evaluations, observing the dynamics of the class, there is no doubt that EPO actively challenged and in some cases, shattered the assumptions of ‘everybody: phones away!’ associated with classroom learning. Screens are generally perceived as a barrier to engagement, yet teachers must contend with the prevalence of laptops for note-taking (though they are not always used in this way). By opening-out this problem and not banishing devices from the classroom, EPO directed laptop and smartphone screens to a positive end, ensuring that if a student was surfing social media in-class, it was for a pertinent reason. Our use of social media in the classroom worked precisely because of the subject matter we handled. Whether Instagram could be brought into the classroom to discuss other subjects is hard to judge, and the answer is probably no. In either situation, EPO indicates that there is potential for classroom teaching to integrate and use social media in the future.

Our primary failure with regard to this project was our lack of strategy in the delivery of Instagram posts. A great deal of planning went into the collection, categorisation, processing and distribution of relevant and meaningful material. However, there were gaps in delivery caused by delays in responses and posting, as well as the difficulties of maintaining a 24/7 educational presence.

Another failure stems from the account’s design and appearance. Many successful Instagram accounts tailor an aesthetic model that brands their images and image composition, e.g. arranging posts in sets of 3, 6 or 9 to create visual uniformity. In comparison to these accounts, which present a carefully curated programme of content, EPO appeared more like a stream-of-documentation, where it is hard to visually discern the shift from one lesson to another.

We also did not employ memes to their full potential. Often we failed to @ students in posts or find the correct angle to engage with them. The right balance between theoretical texts and humorous images was difficult to strike and the public nature of the account may have deterred full engagement. Feedback from students suggests that they did read the memes and were interested in them, but did not feel inclined to converse about them online. Maybe EPO was to an extent, lost in a sea of more interesting content?

These failures point to a single solution: that EPO would have benefited from PR consultation or media training. Undoubtedly this is a somewhat worrying observation, especially when we considering the multiple ‘hats’ teachers in higher education are (already) required to wear.

Whilst there may be resistance to the use of social media in education, there is potential to embrace it and use it to excellent effect. Although Instagram will likely be surpassed by another platform in years to come, the lessons drawn from EPO will hopefully have some future application. Therefore, we conclude this paper with a set of observations that reveal potential options for the deployment of social media within the classroom:

# - a means of associating a post with particular terms (e.g. #glossary) thereby increasing the post’s visibility

@ / @ing - a means of directing a post, or comment, at an individual (e.g. @everybodyphonesout)

❤ - the Instagram equivalent to Facebook’s ‘Like’ functionality, a user may ❤ a post to indicate their approval, ❤s indicate popularity and have some currency characteristics

Comment - communication on a post, each post has its own comments section

Daata Editions - an innovative art gallery exclusively selling digital artworks in limited edition runs (see Gryn 2016)

Followers / Following - Instagram terminology denoting how many users follow one, and how member Instagram users one follows

Gamification - a trend in which social activities are perceived through the logic of video games, now often employed for sales purposes

IBMSN - Image Based Mobile Social Network, the form of social media Instagram belongs to

Instagram - a social media platform on which users post images, typically these images chronicle one’s social life

Instagram Takeover - a form of digital residency whereby an individual is invited to manage an organisation’s Instagram account over a fixed period of time

Insta-verse - the environment of Instagram

Meme - an idea, behaviour, style, skill etc that can be spread from person to person, in digital terms Memes are most prominently a combination of text and image

Meme-esque - something acting in, or appropriating the, form of a Meme

Post - an image uploaded by an Instagram user to their account

Post-Internet - a term that acknowledges that internet art can no longer be distinguished as strictly computer/internet based, but rather, it can be identified as any type of art that is in some way influenced by the internet and digital media (see Olson, 2012)

Prosumer - a person who consumes and produces media

Precariat - social group consisting of people whose lives are difficult because they have little or no job security and few employment rights

Re-post - to share another user’s post on one’s Instagram account via second party software

Student work and comments are presented with full permission of the individuals concerned.

Ba, T. (2016) ‘@amaitriteparole_@sara.frdv @everybodyphonesout #instafood #pizza #foodporn #tasty #lunch #realfood #homemade’, @amaitriteparole Instagram, 24 February. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/BCLL5TTMR0G/ (Accessed: 1 July 2016).

Blackmore, S. (1999) The meme machine. New York: Oxford University Press.Botz-Bornstein, T. (2008) ‘Can memes play games? Memetics and the problems of space’ in Botz-Bornstein, T. (ed.) Culture, nature, memes. Newcastle Upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars. pp. 142-157.Burns, E., MacLachlan, J. and Rees, J.C. (2016a) @everybodyphonesout Instagram. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/everybodyphonesout/ (Accessed: 22 June 2016).

Burns, E., MacLachlan, J. and Rees, J.C. (2016b) ‘Re-post @ryderripps: lesson 1 #feminism #ladies #bae #art #sportswear #camo’, @everybodyphonesout Instagram, 2 February. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/BBSTXyFiO0f/?taken-by=everybodyphonesout (Accessed: 30 June 2016).

Burns, E., MacLachlan, J. and Rees, J.C. (2016c) ‘Re-post @amaliaulman: @amaliaulman #art #women #gyals #instagram’, @everybodyphonesout Instagram, 2 February. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/BBST4LdCO1d/?taken-by=everybodyphonesout (Accessed: 30 June 2016).

Burns, E., MacLachlan, J. and Rees, J.C. (2016d) ‘The work of @raisecain getting discussed in our first lecture #csm #art #instagram #everybodyphonesout’, @everybodyphonesout Instagram, 17 Feb. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/BB5IVPdCOzu/?taken-by=everybodyphonesout (Accessed: 1 July 2016).

Burns, E., MacLachlan, J. and Rees, J.C. (2016e) ‘The further we all move away from humanity, like, sexism becomes the coolest style… because tolerance is inevitable, right?’ @everybodyphonesout Instagram, 22 February. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/BBST4LdCO1d/?taken-by=everybodyphonesout (Accessed: 1 July 2016).

Burns, E., MacLachlan, J. and Rees, J.C. (2016f) ‘Repost: @amaitriteparole_@sara.frdv @everybodyphonesout #instafood #pizza #foodporn #tasty #lunch #realfood #homemade’, @everybodyphonesout Instagram, 24 February. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/BCLMMUMiO4A/ (Accessed: 1 July 2016).

Burns, E., MacLachlan, J. and Rees, J.C. (2016g) ‘Post-new post-internet post-aesthetic Instagram post ✔✔✔✔✔✔✔’, @everybodyphonesout Instagram, 24 February. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/BCLJEfDiOxs/?taken-by=everybodyphonesout (Accessed: 1 July 2016).

Burns, E., MacLachlan, J. and Rees, J.C. (2016h) ‘Sam Sedgman, “what does it mean to “buy” digital art? space” ’, @everybodyphonesout Instagram, 28 February. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/BCVIwYgiO9I/?taken-by=everybodyphonesout (Accessed: 1 July 2016).

Burns, E., MacLachlan, J. and Rees, J.C. (2016i) ‘The EPO Insta Auction House is raking it in!’, @everybodyphonesout Instagram, 2 March. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/BCdKj0BiO56/?taken-by=everybodyphonesout (Accessed: 1 July 2016).

Cornell, C. (2006) ‘Net results: closing the gap between art and life online’, Time Out magazine, 9 February. Available at: http://www.timeout.com/newyork/art/net-results (Accessed: 22 June 2016).Dawkins, R (1989) ‘The Selfish Gene’. Oxford Paperbacks; 2nd Revised edition.Gryn, D. (2016) Daata Editions. Available at: https://daata-editions.com (Accessed: 30 June 2016).Olson, M. (2012) ‘Postinternet: art after the internet’, Foam magazine: issue 29, pp. 59-63. Available at: http://www.marisaolson.com/texts/POSTINTERNET_FOAM.pdf (Accessed: 1 July 2016).

Ripps, R. (2016) @ryder_ripps Instagram. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/ryder_ripps/ (Accessed: 22 June 2016).

Ripps, R. (2015) ‘Feminist artist in Instagram starter pack’, @ryder_ripps Instagram, 1 December. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/-whiNmJTIa/ (Accessed: 30 June 2016).

Sedgman, S. (2015) ‘What does it mean to “buy” digital art?’, Sam Sedgman blog, 8 April. Available at: http://samsedgman.co.uk/post/115845258733/what-does-it-mean-to-buy-digital-art (Accessed: 22 June 2016).

Trecartin, R. (2013) Centre Jenny. Available at: https://vimeo.com/75735816 (Accessed: 22 June 2016).

Trecartin, R. (2016) @ryantrecartin Instagram. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/BCGIc64CO6d/ (Accessed: 22 June 2016).

Ulman, A. (2016) @amaliaulman Instagram. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/amaliaulman/

Ulman, A. (2014) ‘Ok done bak to #natural cuz im sick of ppl thinkin im dumb cos of blond hair.,,,, srsly ppl stop hatin !!how u like me now???’, @amaliaulman Instagram, 27 July. Available at: https://www.instagram.com/p/q9Qc1KFV9M/ (Accessed: 1 July 2016).

Elliott Burns, Jen McLachlan, and Jake Charles Rees are graduates from the 2015 class of MA Culture, Criticism and Curation at Central Saint Martins. Recently they have been employed by UAL as graduate teaching assistants tasked with delivering experimental lessons exploring the potential use of social media technologies in the classroom. Together with other course members they are co-founders of the curatorial collective SPIEL.

Elliott Burns is currently employed by UAL's Teaching and Learning Exchange to curate an exhibition of enquiry-based teaching at the Cook House Gallery in November 2016.

Jen MacLachlan has recently curated several exhibitions, notably at the David Roberts Art Foundation and Chalton Gallery. Her current practice and research interests include photography and semiotics.

Jake Charles Rees is interning for Superflux, a design and foresight studio that investigates emerging technologies and their relationship to society, culture, and politics.